A review of heath economic evaluation practice in the Netherlands: are we moving forward?

Introduction

In the Netherlands, the Dutch National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland or ZIN) is the body in charge of issuing recommendations and guidance on good practice in health economic evaluations, not just for pharmaceutical products, but also in relation to other fields of application such as medical devices, long-term care and forensics. In 2016, ZIN issued an update on the guidance for health economic evaluations, which aggregated into a single document and revised three separately published guidelines for pharmacoeconomics evaluation, outcomes research and costing manual. The novel aspects and future policy direction introduced by these guidelines have already been object of discussion, particularly with respect to the potential impact and concerns associated with their implementation in standard health economics practice in the Netherlands. Given the importance covered by these guidelines, an assessment of their impact on economic evaluation practice is desirable.

The objective of this paper was to review the evolution of health economic evaluation practice in the Netherlands before and after the introduction of the ZIN’s 2016 guidelines. Based on some key components within the health economics framework addressed by the new guidelines, we specifically focus on reviewing the statistical methods, missing data methods and software implemented by health economists. Given the intrinsic complexity of analysing health economics data, the choice of the analytical approaches to deal with these problems as well as transparent information on their implementation is crucial in determining the degree of confidence that decision-makers should have towards cost-effectiveness results obtained from these studies

The ZIN 2016 guidelines

The main objective of the guidelines is to ensure the comparability and quality of health economic evaluations in the Netherlands, therefore facilitating the task of the decision-maker regarding the reimbursement of new health care interventions. Following the example of guidelines issued by decision-making bodies in other countries, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, the recommended features for economic evaluations are summarised in a typical scenario referred to as ‘reference case’, although deviations from it are allowed when properly justified.

Based on the structure of the reference case, four essential components of a health economic evaluation are identified: framework, analytic approach, input data and reporting. For the purpose of the review, we only focus on these components in the reference case as the main elements upon which evaluating health economics practice.

Methods

We performed a bibliographic search in June 2021 using search engines of two online full-text journal repositories: (1) PubMed and (2) Zorginstituut. These sources were chosen to maximise the number of studies that could be accessed given the scoping nature of the review and the lack of a search strategy based on a pre-defined and rigid approach typical of systematic reviews. Articles were considered eligible for the review only if they were cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses targeting a Dutch population. To allow the inclusion of a reasonable amount of studies, the key words used in the search strategy were (cost-effectiveness OR cost-utility OR economic evaluation), and we targeted studies published between January 2016 and April 2021.

Analytic approaches

Almost all reviewed empirical analyses used bootstrapping (95%), although the number of replications varied largely across the studies, with the most popular choices being 5000 (55%) followed by 2000 (29%). Studies showed even more variability in the choice of the methods used in combination with bootstrapping. Seven general classes of statistical approaches were identified, among which unadjusted methods were the most popular choice across both time periods. A clear change in the type of statistical methods used between the two periods is denoted by a strong decrease (from 64 to 39) in the number of unadjusted analyses in 2016–2020 compared to the earlier period, which is compensated by a rise in the number of adjusted analyses using either SUR or linear mixed effects model (LMM) methods.

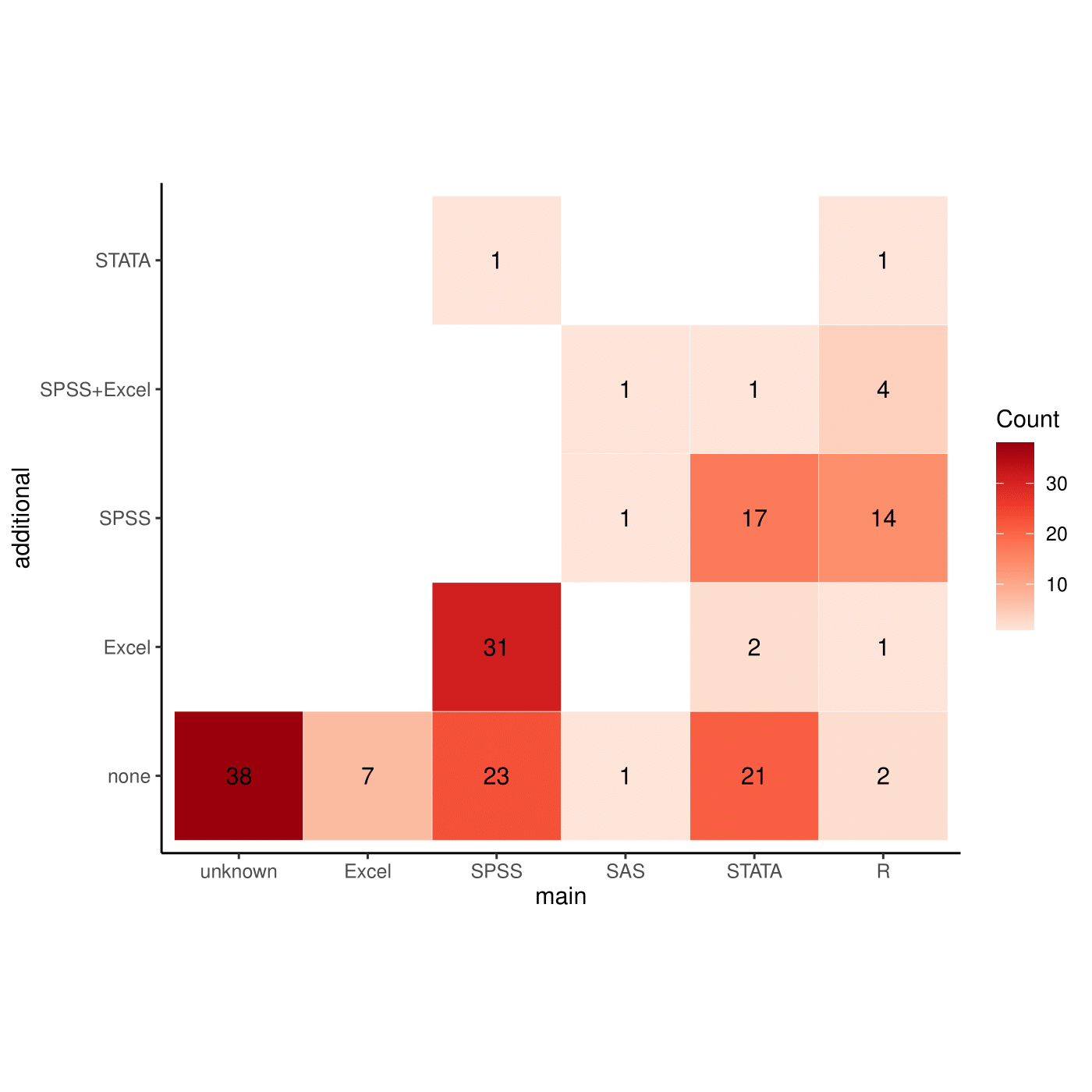

From Figure 1 we can look at the different type and combination of software programs used as an indication of the implementation preferences of analysts for health economic evaluations. Although in principle the choice of software should have no impact on the quality of the statistical methods implemented, it has been highlighted how use of simpler software (e.g. spreadsheet calculators such as Excel) may become increasingly cumbersome for matching more realistic and therefore complex modelling requirements.

The most popular software was SPSS, chosen by 87 (52%) of the studies, either in the base-case (33%) or secondary (19%) analyses, often used in combination with Excel or by itself. When either STATA (26%) or R (13%) was used in the base-case analysis, SPSS was still the most popular choice in secondary analyses. Other combinations of software were less frequently chosen, even though 38 (23%) of the studies were unclear about the software implemented.

Missing data methods

Across both periods limited changes are observed in terms of order of choice for missing data methods, with MI being the most popular base-case analysis, followed by complete case analysis (CCA), as the most popular SA choice. However, two noticeable variations in the frequency of these methods are observed between the two periods. First, the proportion of studies using MI in the base-case analysis has considerably increased over time (from 28 to 39%), which is compensated by a decrease in the proportion of less advanced methods such as CCA (from 14 to 5%) and single imputation (SI) (from 21 to 16%). Second, the number of studies not clearly reporting the methods has also considerably decreased (from 12 to 5%). The observed trend between the two periods may be the result of the specific recommendations from the 2016 guidelines in regards to the ‘optimal’ missing data strategy, resulting in a more frequent adoption of MI techniques and, at the same time, a less frequent use of CCA in the base-case analysis. However, in contrast to these guidelines, a large number of studies still does not perform any SA to missing data assumptions (about 65% in 2010–2015 and 63% in 2016–2020).

Most of the studies lie in the middle and lower parts of the plot, and are associated with a limited or sufficient quality of information. However, only a few of these studies rely on very strong and unjustified missing data assumptions, while the majority provides either adequate justifications or uses methods associated with weak assumptions. Only 11 (14%) studies are associated with both high-quality scores and less restrictive missingness assumptions. No study was associated with either full information or adequate justifications for the assumptions explored in base-case and sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

Descriptive information extracted from the reviewed studies provides some first insights about changes in practice in the years following the publication of the guidelines. First, a clear trend is observed towards an increase in the adoption of a societal and health care perspective and of CUA as the reference base-case analysis approach. Second, a similar increment is observed in the use of recommended instruments for the collection and valuation of health economic outcomes, such as EQ-5D-5L for QALYs and friction method for costs. Most of these changes are in accordance with the 2016 guidelines, which are likely to have played a role in influencing analysts and practitioners towards a clearer and more standardised way to report health economic results.

When looking at the type of statistical methods used to perform the analysis, an important shift occurs between the two periods towards the use of methods that allow for regression adjustment, with a considerable uptake in the use of SURs and LMMs in the context of empirical analyses. These techniques are strongly supported by the 2016 guidelines in that they allow us to correct for potential bias due to confounding effects, deal with clustered data and formally take into account the correlation between costs and effects. Bootstrapping remains the most popular methods to quantify uncertainty around parameter estimates across both periods. However, the health economic analysis framework requires that the level of complexity of the analysis model is reflected in the way uncertainty surrounding the estimates is generated.

The transition between the two time periods reveals an increase in the use of MI techniques in the base-case analysis together with a decrease in the overall use of CCA. This change is in line with the 2016 guidelines which warns about the inherent limitations and potential bias of simple methods (e.g. CCA) when compared to MI as the potential reference method to handle missing values. Nevertheless, improvements are still needed given that many studies (more than 6%) performed the analysis under a single missing data assumption. This is not ideal since by definition missing data assumptions can never be checked, making the results obtained under a specific method (i.e. assumption) potentially biased.

Conclusions

Given the complexity of the health economics framework, the implementation of simple but likely inadequate analytic approaches may lead to imprecise cost-effectiveness results. This is a potentially serious issue for bodies such as ZIN in the Netherlands that use these evaluations in their decision making, thus possibly leading to incorrect policy decisions about the cost-effectiveness of new health care interventions. Our review shows, over time, a change in common practice with respect to different analysis components in accordance with the recent ZIN’s 2016 guidelines. This is an encouraging movement towards the standardised use of more suitable and robust analytic methods in terms of both statistical, uncertainty and missing data analysis. Improvements are however still needed, particularly in the choice of adequate statistical techniques to deal with the complexity of the data analysed and in the assessment of the impact of alternative missing data assumptions on the results in SA.