Bayesian Hierarchical Models for the Prediction of Volleyball Results

Introduction

The type of data used in economic evaluations typically come from a range of sources, whose evidence is combined to inform HTA decision-making. Traditionally, relative effectiveness data are derived from randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs), while healthcare resource utilisation, costs and preference-based quality of life data may come from the same study that estimated the clinical effectiveness or not. A number of HTA agencies have developed their own methodological guidelines to support the generation of the evidence required to inform their decisions. In this context, the primary role of economic evaluation for HTA is not the estimation of the quantities of interest (e.g. the computation of point or interval estimation, or hypothesis testing), but to aid decision making. The implication of this is that the standard frequentist analyses that rely on power calculations and \(P\)-values to estimate statistical and clinical significance, typically used in RCTs, are not well-suited for addressing these HTA requirements.

It has been argued that, to be consistent with its intended role in HTA, economic evaluation should embrace a decision-theoretic paradigm and develop ideally within a Bayesian statistical framework to inform two decisions

whether the treatments under evaluation are cost-effective given the available evidence and

whether the level of uncertainty surrounding the decision is acceptable (i.e. the potential benefits are worth the costs of making the wrong decision).

This corresponds to quantify the impact of the uncertainty in the evidence on the entire decision-making process (e.g. to what extent the uncertainty in the estimation of the effectiveness of a new intervention affects the decision about whether it is paid for by the public provider).

Bayesian methods in HTA

There are several reasons that make the use of Bayesian methods in economic evaluations particularly appealing. First, Bayesian modelling is naturally embedded in the wider scheme of decision theory; by taking a probabilistic approach, based on decision rules and available information, it is possible to explicitly account for relevant sources of uncertainty in the decision process and obtain an optimal course of action. Second, Bayesian methods allow extreme flexibility in modelling using computational algorithms such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods; this allows to handle in a relatively easy way the generally sophisticated structure of the relationships and complexities that characterise effectiveness, quality of life and cost data. Third, through the use of prior distributions, the Bayesian approach naturally allows the incorporation of evidence from different sources in the analysis (e.g. expert opinion or multiple studies), which may improve the estimation of the quantities of interest; the process is generally referred to as evidence synthesis and finds its most common application in the use of meta-analytic tools. This may be extremely important when, as it often happens, there is only some partial (imperfect) information to identify the model parameters. In this case analysts are required to develop chain-of-evidence models. When required by the limitations in the evidence base, subjective prior distributions can be specified based on the synthesis and elicitation of expert opinion to identify the model, and their impact on the results can be assessed by presenting or combining the results across a range of plausible alternatives. Finally, under a Bayesian approach, it is straightforward to conduct sensitivity analysis to properly account for the impact of uncertainty in all inputs of the decision process; this is a required component in the approval or reimbursement of a new intervention for many decision-making bodies, such as NICE in the UK.

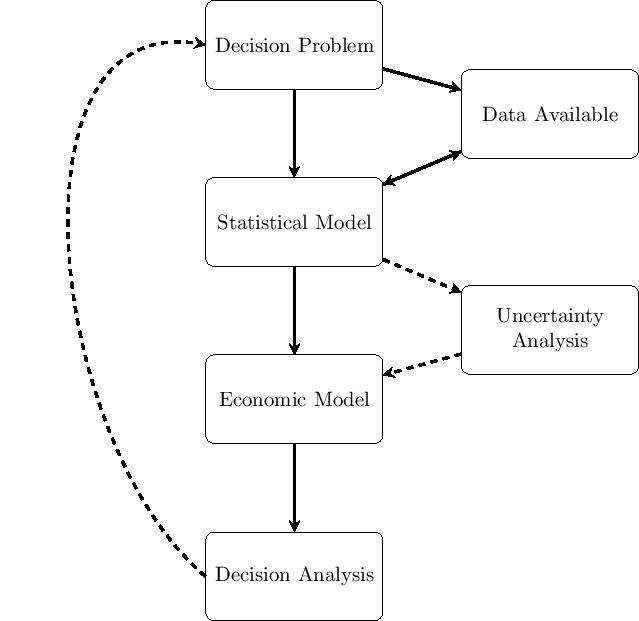

The general process of conducting a Bayesian analysis (with a view of using the results of the model to perform an economic evaluation) can be broken down in several steps, which are graphically summarized in Figure 1.

The starting point is the identification of the decision problem, which defines the objective of the economic evaluation (e.g. the interventions being compared, the target population, the relevant time horizon). In line with the decision problem, a statistical model is constructed to describe the (by necessity, limited) knowledge of the underlying clinical pathways. This implies, for example, the definition of suitable models to describe variability in potentially observed data (e.g. the number of patients recovering from the disease because of a given treatment), as well as the epistemic uncertainty in the population parameters (e.g. the underlying probability that a random individual in the target population is cured, if given the treatment under study). At this point, all the relevant data are identified, collected and quantitatively sytnthesised to derive the estimates of the input parameters of interest for the model.

These parameter estimates (and associated uncertainties) are then fed to the economic model, with the objective of obtaining some relevant summaries indicating the benefits and costs for each intervention under evaluation. Uncertainty analysis represents some sort of detour from the straight path going from the statistical model to the decision analysis: if the output of the statistical model allowed us to know with perfect certainty the true value of the model parameters, then it would be possible to simply run the decision analysis and make the decision. Of course, even if the statistical model were the true representation of the underlying data generating process (which it most certainly is not), because the data may be limited in terms of length of follow up, or sample size, the uncertainty in the value of the model parameters would still remain. This parameter (and structural) uncertainty is propagated throughout the whole process to evaluate its impact on the decision-making. In some cases, although there might be substantial uncertainty in the model inputs, this may not turn out to modify substantially the output of the decision analysis, i.e. the new treatment would be deemed as optimal irrespectively. In other cases, however, even a small amount of uncertainty in the inputs could be associated with very serious consequences. In such circumstances, the decision-maker may conclude that the available evidence is not sufficient to decide on which intervention to select and require more information before a decision can be made.

The results of the above analysis can be used to inform policy makers about two related decisions:

whether the new intervention is to be considered (on average) value for money, given the evidence base available at the time of decision, and

whether the consequences (in terms of net health loss) of making the wrong decision would warrant further research to reduce this decision uncertaint.

While the type and specification of the statistical and economic models vary with the nature of the underlying data (e.g. individual (ILD) level versus aggregated (ALD) data, the decision and uncertainty analyses have a more standardised set up.

Conclusions

HTA has been slow to adopt Bayesian methods; this could be due to a reluctance to use prior opinions, unfamiliarity, mathematical complexity, lack of software, or conservatism of the healthcare establishment and, in particular, the regulatory authorities. However, the use of Bayesian approach has been increasingly advocated as an efficient tool to integrate statistical evidence synthesis and parameter estimation with probabilistic decision analysis in an unified framework for HTA. This enables a transparent evidence-based decision modelling, reflecting the uncertainty and the structural relationships in all the available data.

With respect to trial-based analyses, the flexibility and modularity of the Bayesian modelling structure are well-suited to jointly account for the typical complexities that affect ILD. In addition, prior distributions can be used as convenient means to incorporate external information into the model when the evidence from the data is limited or absent (e.g. for missing values). In the context of evidence synthesis, the Bayesian approach is particularly appealing in that it allows for all the uncertainty and correlation induced by the often heterogeneous nature of the evidence (either ALD only or both ALD and ILD) to be synthesised in a way that can be easily integrated within a decision modelling framework.

The availability and spread of Bayesian software among practitioners since the late 1990s, such as OpenBUGS or JAGS, has greatly improved the applicability and reduced the computational costs of these models. Thus, analysts are provided with a powerful framework, which has been termed comprehensive decision modelling, for simultaneously estimating posterior distributions for parameters based on specified prior knowledge and data evidence, and for translating this into the ultimate measures used in the decision analysis to inform cost-effectiveness conclusions.