set.seed(768)

icc_rasch <- function(theta,b){

p_resp <- (exp(theta - b)) / (1 + exp(theta - b))

return(p_resp)

}

theta_ex <- seq(from = -4, to = 4, by = 0.01)

icc_ex1 <- icc_rasch(theta = theta_ex, b = -1)

icc_ex2 <- icc_rasch(theta = theta_ex, b = 0)

icc_ex3 <- icc_rasch(theta = theta_ex, b = 1)Item-Response Theory: intro

Hello everyone, here we are again with my monthly blog update. Today I would like to continue my initial discussion about Item Response Models (IRMs) which I introduced in one of my previous posts a couple of months ago. In that post I mostly talked about the concept of IRM and how I have become more and more interested in the topic as I believe there is a huge potential for their implementation in the analysis of HE data. I also referred to a very nice book from Jean-Paul Fox called Bayesian Item Response Modelling which I really enjoyed reading this past few months. In this and future posts I would like to extend my initial thoughts about the book and topic and elaborate a bit more about my current understanding of IRMs and how they can used to answer research questions in HE. Today I would like to start this post with an introduction of what are IRMs and how they may be useful to analyse questionnaire data. Most of this information is taken from previous literature on IRMs which for the sake of display I will brutally summarise here to simply get the message through. Please do not blindly trust my posts but think of them as an incentive to check the topics in more depth through an appropriate reference!

Why are IRM needed ?

Initially, IRMs were developed with the objective to analyse item responses in questionnaires collected under standardised conditions for specific types of data. Nowadays, however, their use has become much broader across a wide variety of item-response data which are more routinely collected along surveys or experimental studies and are used for their measurement properties. In addition, the increasing richness and quality of the data collected has posed new and challenging problems at the analysis stage that require the adoption of more sophisticated models that are flexible enough to take them into account; these include: occurrence of item and/or unit non-response, multilevel and longitudinal data structures or respondent heterogeneity. To handle these characteristics of the data, the adoption of more advanced and flexible models allows to avoid relying on simplifying assumptions at the basis of standard statistical methods which, when violated, may distort the results. The Bayesian framework offers a natural approach to deal with these problems that can be summarised as problems related to the quantification of the impact of different levels of uncertainty (e.g. missingness, hierarchical, etc…) on the results of the analysis. Although alternative methods could be used to try to deal with these complex problems (e.g. nonparametric bootstrapping), their implementation becomes exponentially more difficult as multiple features of the data are added into the mix. On the contrary, although Bayesian methods are certainly not needed for the analysis of simple data structures for which the simplicity of standard methods makes them much more appealing to use, their flexibility make them perfect for addressing complex data structures in a relatively easy way through the use of a fully probabilistic approach.

A key concept in the context of IRMs is represent by latent variables, often referred to as latent construct, in that item responses are often assumed to be indicators of an underlying construct or latent variable. IRMs allow the estimation of such construct through the specification of an underlying model structure linking the item responses and the value of the latent variable (supposedly generating such responses). Indeed, the definition of a latent variable that generates the responses allows to reduce the dimensionality of the data thus simplifying the analysis task through the specification of relationships between fewer sets of variables with respect to those measured.

Traditional IRMs: the Rasch model

There is a huge literature on IRM for analysing item-response data but here I will simply focus on one of the simplest and most popular example for the analysis of binary item-responses known as the Rasch Model. In general, key features of all IRMs include the assumption that:

The probability of changing the response to an item depends on changes in the latent variable generating such responses, often mathematically expressed in the form of an Item Characteristic Curve (ICC).

Responses to pair of items are independent given the value of a the underlying latent variable, i.e. assumption of conditional independence.

From the assumptions above, we can then say that: the \(i\)-th respondent associated with a latent construct value \(\theta_i\) has a conditional probability (given \(\theta_i\)) of producing response data \(\boldsymbol y_i\).

In the case of binary responses, one of the simplest and the most widely used IRM is the Rasch model or the one-parameter logistic response model, in which the probability of a correct response is given by:

\[ P(Y_{ik}=1 | \theta_i,b_k) = \frac{\text{exp}(\theta_i - b_k)}{1+\text{exp}(\theta_i-b_k)}, \]

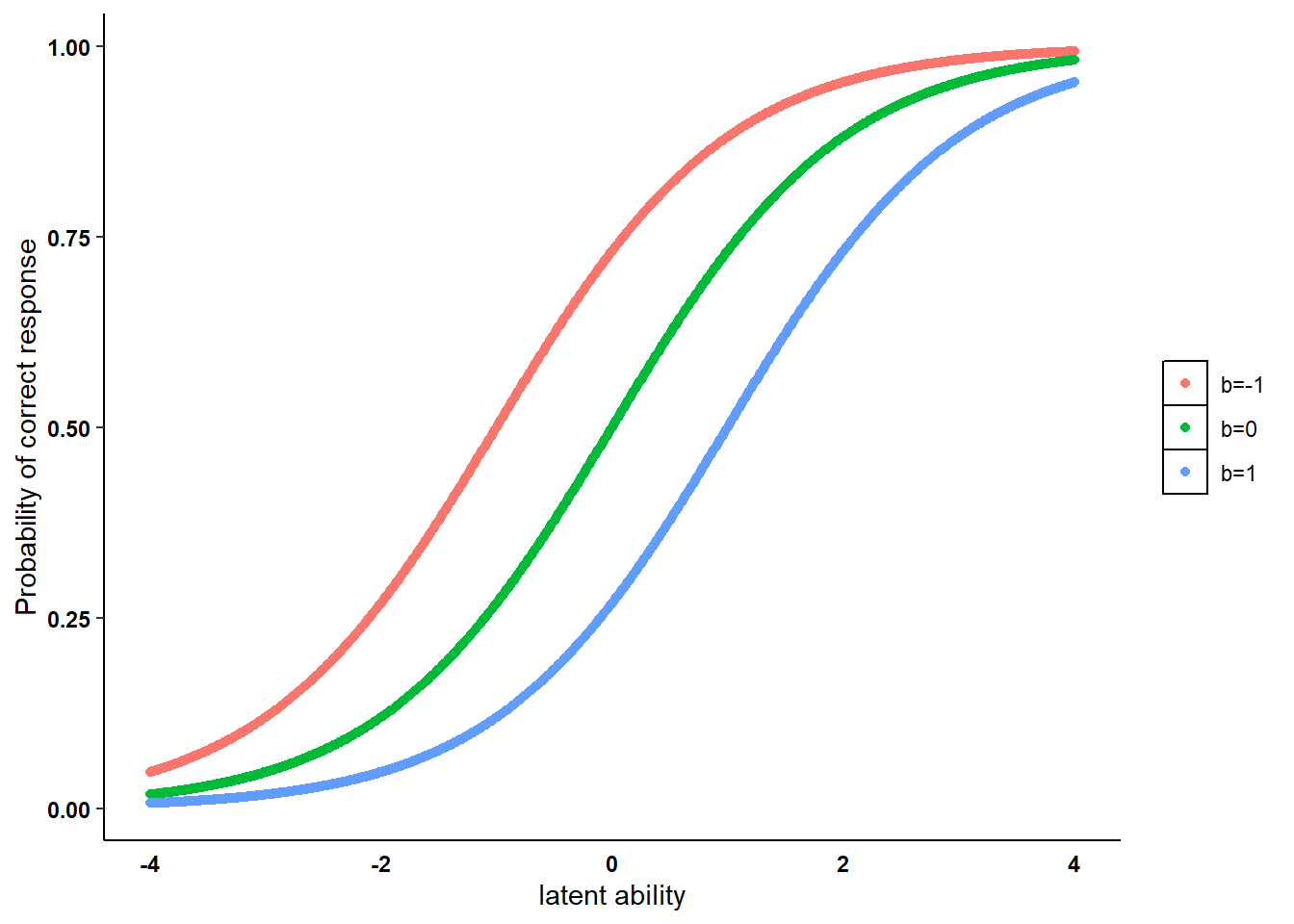

for individual \(i\) with ability level \(\theta_i\) and item \(k\) with item-difficulty parameter \(b_k\). The code below shows how to generate the ICC for the Rasch model in three different scenarios by fixing the value for the item-parameter difficulty (\(-1,0,1\)).

We can then plot the generated ICCs for a range of \(\theta_i\) values to show what the ICC looks like under the Rasch model under each scenario for the item-difficulty parameter \(b_k\).

#plot ICC

library(ggplot2)

n <- length(icc_ex1)

rasch_df <- data.frame(

prob = c(icc_ex1, icc_ex2, icc_ex3),

theta = c(theta_ex, theta_ex, theta_ex),

b = c(rep("b=-1", n), rep("b=0", n), rep("b=1", n))

)

rasch_df$b <- factor(rasch_df$b, levels = c("b=-1", "b=0", "b=1"))

ggplot(rasch_df, aes(x = theta, y = prob, color = b)) +

geom_point() +

xlim(-4,4) +

theme(panel.grid.major = element_blank(), panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

panel.background = element_blank(), axis.line = element_line(colour = "black"),

legend.title = element_blank(), legend.key = element_rect(fill = "white"),

axis.text = element_text(colour = 'black', face="bold"), axis.ticks.x=element_blank(),

strip.background =element_rect(fill="white"), strip.text = element_text(colour = 'black',face = "bold")) + labs(y = "Probability of correct response", x = "latent ability")

Each ICC describes the item-specific relationship between the ability level and the probability of a correct response, with an item defined as easier compared to another when the probability of a correct response is higher with respect to another item given the same level of \(\theta_i\). In the figure it can be seen that the ICCs from the left to the right are associated with increasing item difficulty parameters, with ICCs being parallel to each other. This is a key property of the ICC for Rasch models where for an item an increase in ability leads to the same increase in the probability of success, i.e. the items discriminate in the same way between success probabilities for related ability levels.

Other properties of the Rasch model include:

The probability distribution is a member of the exponential family of distributions which allows algebraic separation of the ability and item parameters.

A response probability can be increased/decreased by adding/subtracting a constant to the ability/difficulty parameter, thus creating an identification problem. This is often solved by the use of some constraints to make the location identifiable, for example by setting the sum of the difficulty parameters equals zero or by restricting the mean of the scale to zero.

All items are assumed to discriminate between respondents in the same way through the item-difficulty parameter.

I hope I was able to summarise the key concept at the basis of IRMs in a sufficiently clear way. The Rasch model provides the simplest and most intuitive modelling approach to represent such scheme and its ICC specification can be used to reduce the dimensionality of binary item responses into a framework where interest is in the estimation of a latent construct representing the individuals’ ability to answer correctly to the questions. The model suffers from some limitations, such as the use of a single item-parameter to discriminate between respondents or the possibility of using the model only for binary data. However, it perfectly embeds the idea behind the use of IRMs: define a theoretical and plausible mathematical structure relating a latent construct that needs to be estimated to the generated answers from the respondents without the need to specify a joint distribution on all responses.

But what about the Bayesian approach? well next time I will try to show why the use of Bayesian framework may be beneficial when estimating Rasch models or, in general, IRMs and how results can be summarised. If this caught your interest, stay tuned!