Back to work

Well those holidays were pretty short in my opinion!

Anyway, time to get back to work and, in fact, it has been already a while since the normal routine started. I try to keep my posts updated as much as I can but with the approaching of the next academic year things are a bit hectic. New and old courses, tutorials, preparation of new teaching material, coordination with other lecturers, consultation with students and researchers, etc… I just need to get back into the mix but sometimes it feels a bit overwhelming. Not that I complain but I just need a bit more time to find the right balance between all these “required” activities and my research which has been left a bit behind if I want to be honest. Hopefully, in a couple of months things will slow down and I will have some free to time to continue doing some nice research work. I really miss that now !

Enough about my lamentations, let’s see if there is someting interesting that I can talk about in this, otherwise, plain post. Well I always wanted to give my opinion on a very interesting, although now a bit dated (2001), health economics article by the emeritus professor Antony O’Hagan, to my knowledge still working at the University of Sheffield. This I think the first general health economics publicaton addressing the topic of the need to develop a consistent and flexible statistical framework for the analysis of health economic individual-level data. The article is entitled “A framework for cost-effectiveness analysis from clinical trial data” and is a marvellous example of what many people have replicated and expanded over the following years (including myself), namely the call for a comprehensive analysis framework which can be generally applied for the analysis of cost-effectiveness data which takes into account the typical statistical issues that characterise these types of data.

Indeed, for many years health economists did not rely on a solid general approach for the modelling and analysis of the data collected from clinical trials as in most cases focus of health economics literature was on decision modelling or aggregated data analysis, with little methodological emphasis on how practitioners involved in clinical studies should handle the specific problems that affect these data, i.e. from missingness, bivariate outcome, covariate adjustment, etc… Antony’s paper was for sure the first reading I was exposed which provided an idea on how things could be done in a more consistent way through the introduction of a Bayesian analysis framework and a clear justification for the adoption of this statistical approach in the field of health economics. This was already explored in the past by other authors (e.g. Claxton for sure was one of the first ones recognising the advantages of using a Bayesian approach) but no clear guidelines or implementation modelling strategy was available for standard analysts to look at.

In my opinion this is a very underrated publication and someone may disagree with me when I say that I find this to be a milestone in the statistical analysis literature of health economic data. I rarely see this paper cited in modern articles or publications, although many of these propose a similar concept to the one Antony gave in his paper, i.e. the call for a statistically-sound and reliable analysis framework that analysts may replicate in their analyses to obtain more consistency in the methodology used as well as taking into account the possible problems affecting the data that may lead to biased results. Of course, today things have changed and new publications provide more advanced and alternative approaches to deal with these problems, but the general concept behind this stil remains the same and I think we all owe, at least partially, Antony for what he tried to achieve with his paper. I am not sure how much his work influenced current health economics practice but it has for sure affected me and my research considerably.

I would encourage any health eocnomist to read this paper as it gives a nice picture of why a statistical framework for the analysis of cost-effectiveness data is something that is desirable and that people should try to implement in thier analyses. Key aspects include the possibility to:

Specify the model for effect and cost data in a flexible way by expressing the mean population parameters for the two outcomes as functions various model parameters

The advantages provided by the Bayesian framework to implement this framework while also naturally accommodating the propagation and quantification of uncertainty surranding the parameters of interest

The convenience of using this framework to handle statistical issues such as correlation between outcomes, covariate adjustment, and provision of standard output such as cost-effectiveness planes and curves

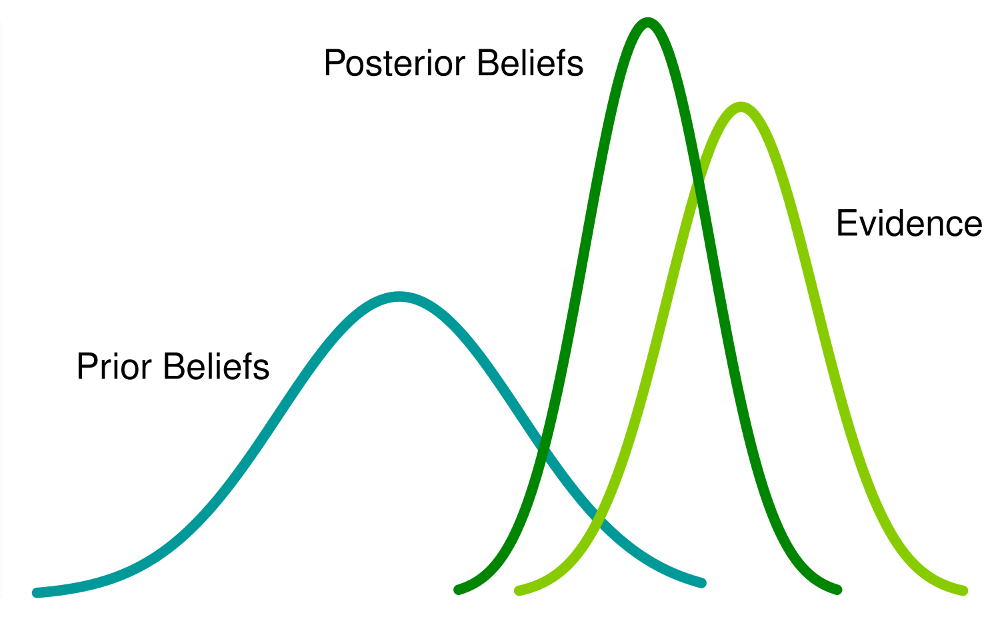

There is also a clear “defense” of the use of prior information in regard to the modelling of these parameters within a Bayesian framework. Long story short, appropriate use of informative priors does not bias the inferences in the sense of favouring one treatment over another in a “subjective” way. Prior information is essentially an extra tool available to analysts which may also be the only way to incorporate some external information (i.e. expert opinion) into the model which would otherwise be discarded therefore resulting in an effective loss of information. Of course, it is important that the way this information is elicited into the model is reasonable and that it actually reflects the information available from external sources. However, there are plenty of ways to perform these assessments to check this in a rigorous way. I find it annoying that people would discard the use of prior information simply because they are not “sure” it is correct to use it. As any source of information, external information is information and as such it would inefficient, whenever this is available, to ignore it. Sometimes ignoring this information may lead to biased conclusions as well, e.g. in the case of missing data where observed data information may not be enough to obtain reliable results.

In such cases, wouldn’t be more reasonable, although I agree more difficult, to think about what type of other information is available to us and how this can be incorporated into our analysis in order to better assess the robustness of our results compared to, say, simply cover our eyes and pretend no information exists?