The P value fallacy

Today, I would like to briefly comment an interesting research article written by Goodman, who provided a clear and exemplary discussion about the typical incorrect interpretation of a standard frequentist analysis in the field of medical research. I will now briefly summarise the main argument of the paper and then add some personal comments.

Essentially, the article describes the characteristics of the dominant school of medical statistics and highlights the logical fallacy at the heart of the typical frequentist analysis in clinical studies. This is based on a deductive inferential approach, which starts with a given hypothesis and makes conclusions under the assumption that the hypothesis is true. This is in contrast with a inductive approach, which uses the observed evidence to evaluate what hypothesis is most tenable. The two most popular methods of the frequentist paradigm are the P value proposed by Fisher and the hypothesis testing developed by Neyman and Pearson.

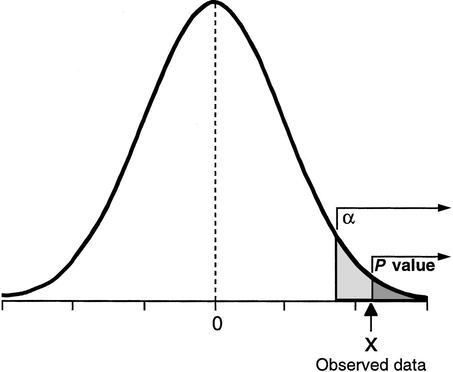

The P value is defined as the probability, under the assumption of no effect (null hypothesis), of obtaining a result equal to or more extreme than what was actually observed. Fisher proposed it as an informal index to be used as a measure of discrepancy between the data and the null hypothesis and therefore should not be interpreted as a formal inferential method. For example, since the P value can only be calculated on the assumption that the null hypothesis is true, it cannot be a direct measure of the probability that the null hypothesis is false. However, the main criticism to the P value is perhaps that it does not take into account the size of the observed effect, i.e. a small effect in a study with a large sample size can have the same P value as a large effect in a small study.

Hypothesis testing was proposed by Neyman and Pearson as an alternative approach to the P value, which assumes the existence of a null hypothesis (e.g. no effect) and an alternative hypothesis (e.g. nonzero effect). The outcome of the test is then simply to reject one hypothesis in favour of the other, solely based on the data. This exposes the researcher to two types of errors: type I error or false-positive (\(\alpha\)) and type II error or false-negative (\(\beta\)) result. Rather than focussing on single experiments, like the P value, hypothesis testing is effectively based on a deductive approach to minimise the errors over a large number of experiments. However, the price to pay to obtain this objectivity is the impossibility to make any inferential statement about a single experiment. The procedure only guarantees that in the long run, i.e. after considering many experiments, we shall not often be wrong.

Over time a combination between the P value and hypothesis testing was developed under the assumption that the two approaches can be complementary. The idea was that the P value could be used to measure evidence in a single experiment while not violating the long run logic of hypothesis testing. The combined method is characterized by setting \(\alpha\) and power \(\beta\) before the experiment, then calculating a P value and rejecting the null hypothesis if the P value is less than the preset type I error rate. This means that the P value is considered a false-positive error rate specific to the data and also a measure of evidence against the null hypothesis. The P value fallacy is born from this statement, which assumes that an event can be seen simultaneously from a long run perspective (where the observed results are put together with other results that might have occurred in hypothetical repetitions of the experiment) and from a short run perspective (where the observed results are interpreted only with respect to the single experiment). However, these views are not reconcilable since a result cannot be at the same time an interchangeable (long-run) and unique (short-run) member of a group of results.

I personally find this discussion fascinating and I believe that it is important to recognise the inconsistencies between the two alternative approaches to inference. The original authors of the two paradigms were well aware of the implications of their methods and never supported the combination of these. However, the combined approach has somehow become widely accepted in practice while its internal inconsistencies and conceptual limitations are hardly recognised.

I feel that, since the two methods are perceived as “objective”, it is generally accepted that, if combined, they can produce reliable conclusions. This, however, is not necessarily true. Accepting at face value the significance result as a binary indicator of whether or not a relation is real is dangeroues and potentially misleading. This practice wants to show that conclusions are being drawn directly from the data, without any external influence, because direct inference from data to hypothesis is thought to result in mistaken conclusions only rarely and is therefore regarded as “scientific”.

This misguided approach has led to a much stronger emphasis towards the quantitative results alone (without any external input). In contrast, I believe that such perspective has the serious drawback of ignoring potentially useful information which is available (e.g. relevant medical knowledge or historical data) and which should be included in the analysis. Of course, I am aware of the potential issues that may arise from the selection and incorporation of external evidence, but I believe this should not be considered as “less reliable” or “more prone to mistakes” compared with the evidence from the available data. It is important that an agreement is reached about the selection of the type of evidence and methods to be used to perform the analysis solely based on their relevance with respect to the context analysed.